Curators All the Way Down

By Gaby Goldberg and Jesse Lee. Originally published on Mirror.

Introduction

Last year, I published the piece Curators are the New Creators, arguing in favor of a business model centered around “good taste.” This piece expands upon that previous work by putting a magnifying glass on the relationship between curation and commerce. I’m grateful and excited to be writing it with Jesse Lee of Basic.Space, who’s helped to illuminate the unique relationship between goods and tastemakers.

In 1997, Malcolm Gladwell published his piece The Coolhunt, investigating the process of looking for new fashion trends at street level.

According to Gladwell, the coolhunter plays a major social role in spreading trends. Coolhunters were “the first to realize… that social status didn’t lay where Madison Avenue had said it lay in the 1950s and 1960s and 1970s — in people with the most education, the most money… [Coolhunters set] that paradigm aside” and placed value instead on personal influence. These were individuals who mastered their crafts by consuming large amounts of information — style, culture, behavior — and figuring out how to digest it all before anyone else. Gladwell argued that the rest of us “rely disproportionately” on these coolhunters when it comes to making decisions.

We’ll come back to Gladwell later in this piece. But to better connect the dots, let’s first jump to 2011, just over a decade later, when Marc Andreessen published Why Software Is Eating The World in a Wall Street Journal op-ed.

Andreessen’s idea was prescient. At the time, many people thought the future had already arrived. The iPhone was four years old; Facebook had nearly 850 million users. The Internet had changed everything; it seemed there was nowhere else we needed to go.

Of course, Andreessen proved those people wrong. Uber launched its service in 2010, and Airbnb reached 1 million listings in 2014. Just as he had predicted, companies across just about every traditional, non-tech industry began thinking and acting like a software company.

What Marc Andreessen understood at this tipping point was that technological innovations — like in transportation, with Uber, and hospitality, with Airbnb — often emerge when it seems we need them least.

So it’s fitting that exactly a decade later, we’ve come to another watershed moment. Software has eaten the world, and now it’s a commodity. It’s not about the technology anymore. The era of the engineer has ended; the era of the curator has begun.

We can combine the lessons learned from both Gladwell and Andreessen when we look at today’s consumer behavior and purchasing culture. The success of social networks like Tumblr and Instagram over the last two decades helped usher in a transformative shift in how people interact with information online.

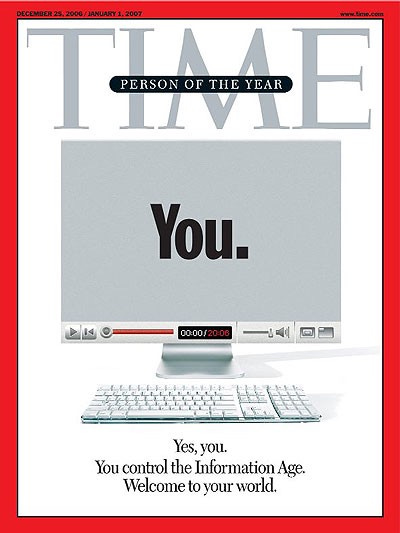

While Web 1.0 in the ’90s and early 2000s was static and read-only, Web 2.0 was social and interoperable. This new wave of the Internet emphasized user-generated content and participation across nodes of the network. In 2006, the growing influence of Web 2.0 was acknowledged by TIME Magazine’s Person of The Year:

The magazine told a story of “community and collaboration on a scale never seen before. It’s about the cosmic compendium of knowledge Wikipedia and the million-channel people’s network YouTube and the online Metropolis MySpace.” And we were only scratching the surface. In 2006, MySpace was the most visited website on the planet; by 2008, it was eclipsed by Facebook. Instagram and Pinterest came on the scene in 2010, and Snapchat in 2011. Five years later, in 2016, the term influencer was officially defined on Dictionary.com — and its prominence only went up from there.

The combination of all these factors helped lead to what we call today the creator economy, a growing segment made up of the “independent businesses and side hustles launched by individuals who make money off of their knowledge, skills, or following.” New companies emerged across all verticals to fit these creators’ growing needs: Cameo for fan interactions, Stir for financial tooling, Commsor for community, Maven and Metafy for online courses, Makersplace for NFTs, and a host of others. This year alone, over $1.3B has been invested into the space.

The shift to putting creators in the driver’s seat was a long-awaited one. But no good thing comes without unintended consequences. Users were uploading 300 hours of video to YouTube every single minute; over 100 million photos were posted to Instagram each day. Even when we look today, it’s impossible to keep up with the number of new Tweets, emails, blog posts, or Google searches every second.

In short, with democratized access, the web became more saturated than ever before, and as consumers, we began to spend more and more time trying to sort through it all. In a state of analysis paralysis, how do we disaggregate signal from noise?

This problem of overabundance is why I wrote my piece last year. As consumption of digital media increased, we began to see a larger volume of curators — coolhunters, just like Gladwell had outlined in ’97, but this time in a digital space. On Tumblr, this looked like blogs of curated art or photography; on Pinterest, we saw well-crafted collections of clothing, recipes, or furniture. Even on Instagram, curated meme accounts like @thefatjewish and @fuckjerry exploded in popularity due to their easily digestible and shareable content.

But being a curator isn’t as simple as it might seem. In what we like to call the Social Media Paradox, there’s an often overlooked difference between following someone to be entertained and following someone to make a purchase. Put simply, influence is not synonymous with taste. This misunderstanding plays out in real-time: some influencers have large followings but still struggle to monetize, while others — oftentimes curators, or coolhunters — can successfully monetize without developing an image or personal brand. We’ve seen this particularly over the last few years, as a myriad of primarily anonymous Instagram accounts like HIDDEN®, Nineties Anxiety, Furniture Archive, and New Bottega have risen in influence as prominent tastemakers for the next generation of fashion and culture.

“You have to be obsessed with the media to keep up. In my opinion, a constant stream of your favorite things is much more telling than photos of your day to day life… my followers know me much more intimately than a typical influencer.”

— HIDDEN® in Highsnobiety

Of course, these Instagram accounts weren’t the first curators to reach the digital mainstream. Kanye West’s impact in music and production helped pave the way in this domain, building a multi-billion dollar enterprise via fashion and design. On the music front, Kanye directly influenced rappers like Travis Scott, Kid Cudi, Chance the Rapper, and Big Sean. Even Drake and the Weeknd come from Kanye’s lineage to some degree. And in terms of design, Kanye is not a technical designer as much as an arbiter of cool, with a team of creative talent to help realize his vision. Kanye continually pushes the curation flywheel forward: some of the people who worked on his team over the last decade are now wildly successful creatives and designers themselves, including the likes of Virgil Abloh, Matthew Williams, Heron Preston, and Jerry Lorenzo. Now, these people are the coolhunters, the ones searching on the ground floor for people like HIDDEN® and his counterparts.

In The Coolhunt, Gladwell wrote that fashion trends used to be set by the big couture houses — when cool was trickle-down. “But sometime in the past few decades things got turned over, and fashion became trickle-up.” He was exactly right.

Now, culture is more decentralized than it’s ever been.

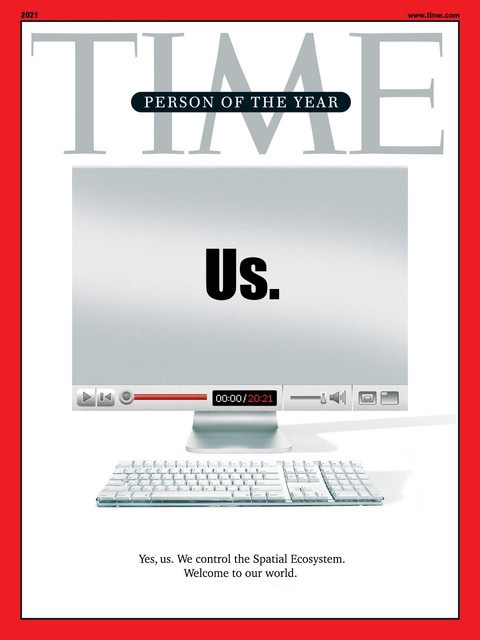

Just like we saw in TIME’s 2006 Person of the Year — if Web 2.0 was all about you, then Web 3.0 is all about us.

When we look back over the past 100 years, traditional commerce (and the culture it indirectly endorsed) was primarily curated by a single person’s point-of-view. Even when commerce moved online, to places like Amazon or Farfetch, retailers still controlled the types of things consumers purchased. Online commerce didn’t innovate a new shopping experience; it just brought brick-and-mortar to online. This was an improvement in convenience, not fidelity. To be clear, this model didn’t include consumers in the equation, because it didn’t need to.

Now, in today’s state of overabundance, this power dynamic has shifted. Consumers are only getting smarter, and we want something better — better sources, better designs, and better durability (both in value and sustainability). Today, it’s fidelity over convenience. And when curation is at the forefront of every purchasing decision, trust is currency.

It’s why we see success in companies like Basic.Space, which sits at the intersection of curation and commerce. By curating not just products but sellers, too, Basic Space celebrates the rugged individualists of tomorrow while simultaneously giving the rest of the world direct access. This is how curation scales.

As Marc Andreessen told us in his 2011 op-ed, innovations in technology often occur when it seems we need them least. Today, buying products online has never been easier. Convenience is at an all-time high, and consumers have more options than ever before. It seems, once again, that there is nowhere else we need to go. And yet, this is precisely the problem.

In today’s oversaturated world, we need curators to help us separate signal from noise. Gladwell told us about coolhunters in ’97, and they’ve now emerged as a solution in digital space. Culture is officially trickle-up; to tell us where to go, we believe it’ll be curators all the way down.

Cover artwork by Ilya.

Thank you to Alex Mahedy, Tyler Angert, Tony Lashley, Brian Flynn, Erik Torenberg, Adi Sidapara, Ian Kar, and Nick Sarath for their thoughts and feedback. Most of all, thank you to Jesse Lee for the opportunity to collaborate on such an energizing and forward-thinking piece.